The Lesson from Walid

If there is one little factoid that the punditocracy has, over the past month, not hesitated to beat the proletariat over the head with, it is that no World Cup winner has ever been helmed by a manager of foreign extraction.

It is one of those truths that do not sound quite right the first time you hear them, especially considering that migration and cross-pollination of ideas have underpinned the development of football across the globe. Still, it is patently so; the 2022 Mundial will only further that unlikely record, as Didier Deschamps and Lionel Scaloni pit their wits against each other at the Iconic on Sunday night.

So, what is it then? Is the key to success at the World Cup somehow wrapped up in the appointment of an indigenous manager? After all, it is not simply the case that the winners fit the criteria; the same is true for the runners-up as well, and it holds stretching to the final four as well. Going back 12 editions, there are only two instances of a semi-finalist managed by a foreigner - Korea, with Guus Hiddink in 2002, and Belgium, led by Roberto Martinez in 2018. There does seem to be a strong correlation.

As we know, though, that does not necessarily suggest causality. The flaw with decision-making on the basis of precedent is that it can lead to a cycle of perpetuation, wherein the only way to succeed is to do what others have done in order to succeed. What that ignores is the place of innovation: the first person who ever succeeded in that fashion was, by necessity and definition, breaking new ground. So the more that template is adopted (thereby increasing the statistical likelihood of a favourable outcome), the more its prescriptive status is calcified.

(An example of this reasoning can be found in the now-prevalent idea that the way to win international tournaments is to play defensively. Conveniently, the teams that win without installing defence at the top of their tactical hierarchy (e.g Spain in 2008, Germany in 2014, Italy in 2020) are either erroneously termed defensive on account of having a balanced shape that lends itself to clean sheets, or are ignored outright.)

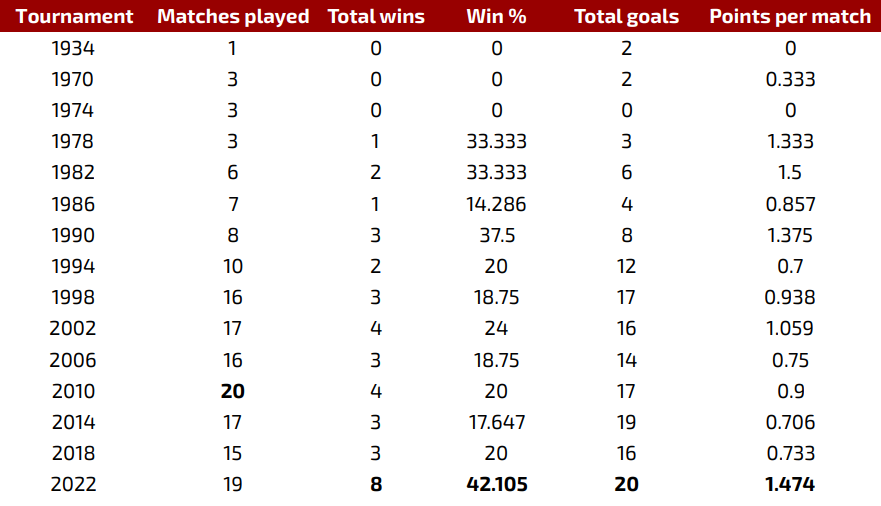

There is a readiness, now more than ever, to embrace the indigene as the ideal coaching hire for African sides. The impetus for this is not difficult to understand: in 2022, for the first time ever, all five African representatives are led by managers of local extraction. The result has been the continent’s best-ever performance at the World Cup in every statistical metric. For the first time since the continent’s allotment rose above one, every African side picked up at least a win; for the second time ever, two African sides progressed beyond the Group Stage; for the first time ever, an African side reached the semi-finals.

The wild success of Walid Regragui, among others, is now being held up for the possibility it hints at. While this is understandable, it would be a mistake to conclude that appointing indigenous coaches is some sort of panacea, especially for African nations.

In many ways, Qatar 2022 is a confluence of many factors: Maher Mezahi has advanced the interesting theory of home field advantage, for one; there is also the absence of truly outstanding national sides (interesting, isn’t it, that the more national teams have focused on being defensive in the service of winning, the fewer historic teams there are?), allied to the fact that African sides have reaped the benefits of globalisation more than at any previous World Cup (a staggering 41.5 percent of players were born outside of Africa). This latter factor has led to a shrinking of the quality gap to a significant extent, notable when viewed in conjunction with the even briefer turnaround time before the commencement of this tournament.

This is not to say entrusting the national team to an indigenous coach achieves nothing. On the contrary, there are a number of potential benefits, chief of which is the psychological element. Simply put, there is a grasp of self-image and psychology, both on an individual and socio-cultural level, that can only come of having been formed in the same crucible as the players themselves.

Having been touched with the feeling of their infirmities, as it were, the indigenous coach can better understand what strings to pluck in order to elicit the desired reaction on a case-by-case basis. This is crucial for buy-in, not just from the players, but from the watching public, to whom the national team invariably belongs.

Managers without that lived experience to call upon will often jar with the public and the press, unable to understand why, even in the presence of relatively healthy results, they are not more accepted. This precise dynamic played out in Morocco, where Vahid Halilhodzic was, for all intents and purposes, successful, but constantly fell out with important players and was deeply unloved. Regragui, appointed less than three months to the start of the World Cup, was able to repair the cracks in the squad and obtain buy-in ahead of a historic run.

I am a little less unequivocal than Fiifi Anaman on this matter, but it is certainly the case that, in an ideal world, it is infinitely preferable that a national team be led by an indigenous coach. (The nature of identity is a gnarly subject, but I would be uncomfortable denying, say, a foreigner who has invested a lot of knowledge and emotion into football on the local scene equal opportunity in the reckoning for the national team job.)

However, it is important that, in garnering lessons, one garner the right ones. The moral here is not that simply turning over the national team to a local coach is the way to go. If Regragui is the case study, then it would be necessary to show the same level of commitment to the development of coaches in your country as Morocco have over the past decade. When, six months ago, 23 coaches of African extraction earned the inaugural CAF Pro Licence, it was striking that 20 of them were Moroccan. In order to participate, it was required that the coaches, among other things, already hold the equivalent of the CAF A Licence.

Under these stringent conditions, how many coaches in your country would qualify? In Nigeria, for instance, the state of coaching education is, to put it mildly, pitiful.

Beyond even the certification, consider also the amount of experience Regragui accumulated before stepping into the role. The former Morocco international has been practising for the better part of a decade, and has been tested in various roles in many different countries and cultures, with degrees of success. This has led to a refining and sharpening of ideas, enabling him to step into a most exacting brief with assurance.

While this is not the case for all of Africa’s coaches in Qatar, it is certainly so for most. Aliou Cisse is one exception; nevertheless, in lieu of prior managerial chops, he has been afforded the leeway to learn on the job over the course of seven years, even in the face of early underachievement. (Rigobert Song, the other exception, is impossible to parse without complete digression.)

Clearly, even accepting the advantages a local coach brings to the table, appointing one is, by itself, no guarantee of success. There must also be proof of concept, in the form of both the highest possible certifications and proper coaching chops (with success, it goes without saying) in smaller roles. This must be underpinned by the correct attitude, from the football administration, toward the development of coaches within its own territory, as well as by a long-term commitment in the form of patience and professionalism.

Then, and only then, will appointing an indigenous manager be best practice.

A true wordsmith! 👏

Yet again, another masterpiece.

As is the case in many aspect of governance in Nigeria, installing men without the know-how and zero commitment in positions of power is making simple issues unnecessarily difficult. Surely, one would think making reasonable effort to effect sustained change in the quality of sports in Nigeria is beyond Sunday Dare, a man who oversaw the cutting of grass for a whooping 80 million, so too Amaju Pinnick, a man who is more consumed by his quest of being FIFA royalty than he is of overseeing any positive change in the sport under his watch to think of the dearth of quality in the local coaching scene.

The problem? We keep expecting mangoes from citrus tree. We want mangoes? Easy! Cut down the citrus tree and plant mango.

At best, what is obtainable in Nigeria currently is a repeat case of Aliou Cisse's learning on the job and I personally think that ship has sailed considering the quality of players currently in the national team set up is a precipice of clamour for instant success by fans. The commitment or lack of it of the players to the cause poses another question entirely.