Do the Eagles pass the Duck Test?

In most relevant metrics, Nigeria are (so far) hanging with Africa's elite at the ongoing Africa Cup of Nations.

The mood going into Nigeria’s 2025 Africa Cup of Nations Round of 16 tie against Mozambique could not be more different than what obtained coming into the tournament. Indeed, for the first time since probably the last edition, there is a sense of anticipation around the Super Eagles.

It is not simply the case that the Mambas are firmly the underdog, nor is it entirely down to a perfect group stage campaign for the three-time African champions. Both of those circumstances have been replicated previously, incidentally rarely to good effect. This time, the main source of optimism is a sense of culmination: having laboured through a year’s worth of sludge, the fruit of Eric Chelle’s football is finally in evidence.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in the defeat of Tunisia. For over an hour, Nigeria held the North African side mostly at arm’s length, smothering them with a mix of speed and intensity that was, at times, irrepressible. That was the ideal, the ultimate expression of Chelle’s vision, his dream made flesh. The satisfaction was not solely his, either: the game’s third, blasted in by Ademola Lookman, was one of the goals of the tournament, a flowing team move that married timing and decision-making with immaculate execution to titillate an entire continent. It was a reminder, internal and external, of the quality that this group boasts, a fact that has been sadly obscured by the failure to qualify for next year’s World Cup.

It has not been perfect, however. Not by a long shot. In much the same way as we have witnessed performances that have defied the Super Eagles pre-AFCON form, we have also seen some of the same foibles that marked it. Chief is the chronic inability to keep clean sheets, so much so that, even dead, buried and down to 10, a sorry Uganda side were still able to run through and snag a consolation. This lack of resistance, then, makes it difficult to gauge the true competitive level of this side.

There is enough to suggest, even beyond the top-line numbers, that Nigeria have been one of the leading sides in Morocco. The Super Eagles lead the tournament in scoring, despite having only the third-highest cumulative Expected Goals (xG) total, behind only Senegal and Morocco, the two big favourites coming in. Central to this has been some overperformance in terms of conversion, although any concerns around that are offset somewhat by the wastefulness of Victor Osimhen—in a way, it is ominous for the rest of the field that the tournament’s star centre-forward has yet to properly hit his stride.

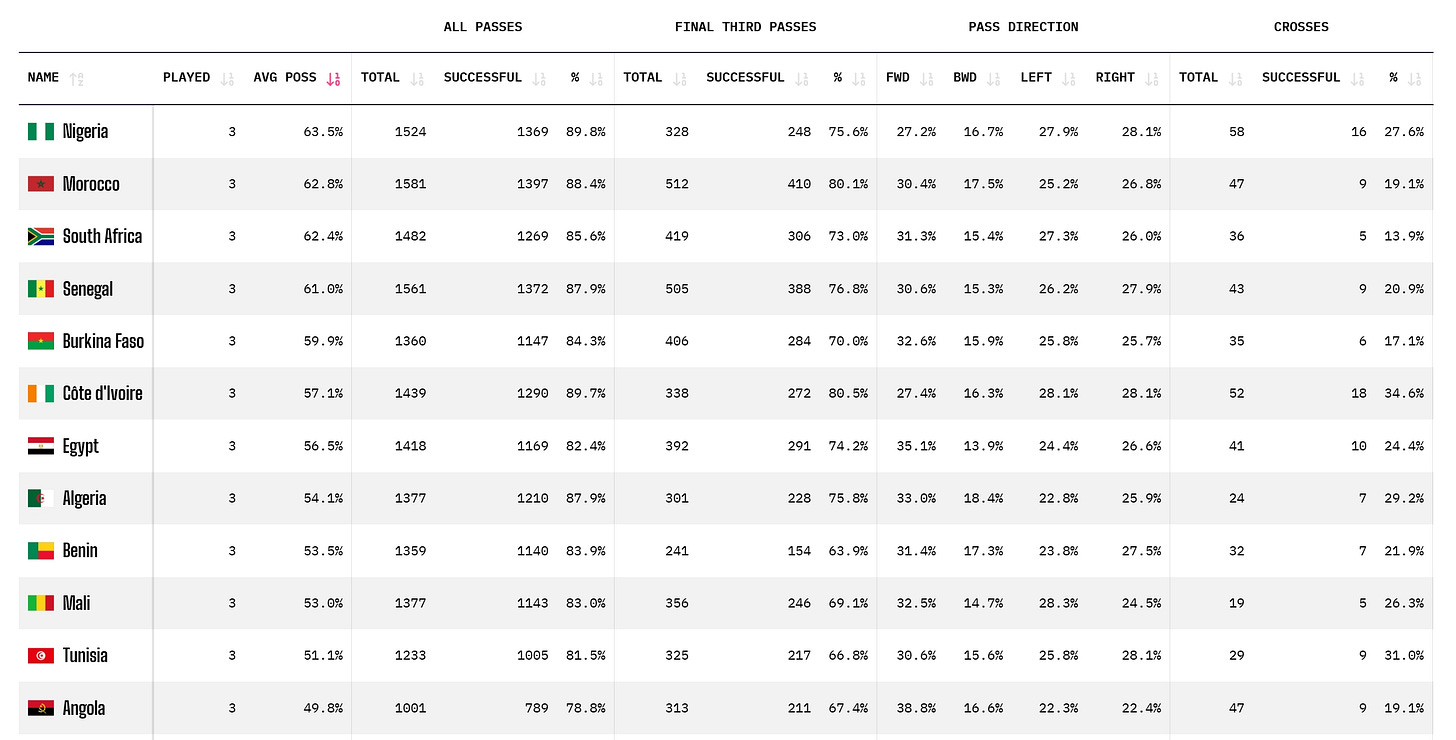

In terms of ball usage, Nigeria lead the way in average possession and sequences of 10 or more passes, and rank as the team with the lowest proportion of passes played forward, with 27.2 per cent. This is in keeping with the elite, often burdened with the imperative to dictate and carefully break down less ambitious opposition; Cote d’Ivoire and, again, Morocco and Senegal feature close by, all circulating and probing for the most part until an opening presents itself. The only significant deviations in Nigeria’s case are in terms of passes attempted into the final third where, even though the success rates are in line, there is much less volume (unsurprising considering the burden of this is inordinately shouldered by one player – Alex Iwobi. More on this later.); and in what happens when the ball goes wide, as the Super Eagles have attempted crosses more readily. The numbers paint a picture: Chelle’s side keep the ball, attack deliberately, pick their moments to penetrate, channel much of their circulation wide, and cross a lot.

Where things start to diverge, however, is on the defensive end of the spectrum.

While they have been punished inordinately based on the quality of chances they have conceded (four goals conceded, despite giving up 2.6 xG), the Super Eagles have allowed more touches inside their box and given up more shots than Gabon and Benin. The opponent is getting lucky, but the closer to goal they are when they scratch the lottery ticket, the easier it is for finishing quality to be brought to bear. A further cause for alarm is that Nigeria have blocked the same number of shots on their goal as Morocco, who have fielded only half as many shots, and Cote d’Ivoire, who have allowed 12 fewer. Considering an xG/shot ratio of 0.09, it is hardly the case that they are constantly giving up one-on-ones—this, instead, points to a loss of defensive intensity and/or concentration inside their own penalty box, notably as a result of fatigue.

Fun fact: an eye-watering 66 per cent of Nigeria’s conceded xG has come in the final 25 minutes of their matches.

The reason for this fatigue is, of course, the side’s default approach without the ball. In keeping with the desire of their head coach, the Super Eagles are voracious in their pressing appetite. On average, the opposition only manages 7.7 passes before Nigeria complete a defensive action, be that a foul, tackle, interception or challenges. That is the second-best figure for any team in the competition in terms of intent to pressure; they are also second for pressed sequences (according to Opta, the number of open-play sequences starting in their defensive third where the opposition has three or fewer passes, and the sequence ends in their own half), and play the third-highest line.

All of that physical exertion is bound to take a toll later on in matches, a fact that Chelle accepts—ideally, the aim would be to build up a healthy enough advantage that, when his players inevitably hit a wall, there is a safety net. However, considering that the Super Eagles do not exactly go directly at the opponent’s throats when they win the ball, one would expect them to not deplete quite so dramatically; resting with the ball seems to be (part of) the idea. The reason for the fatigue is not so much the pressing itself as it is the inefficiencies of the structure within which the team presses.

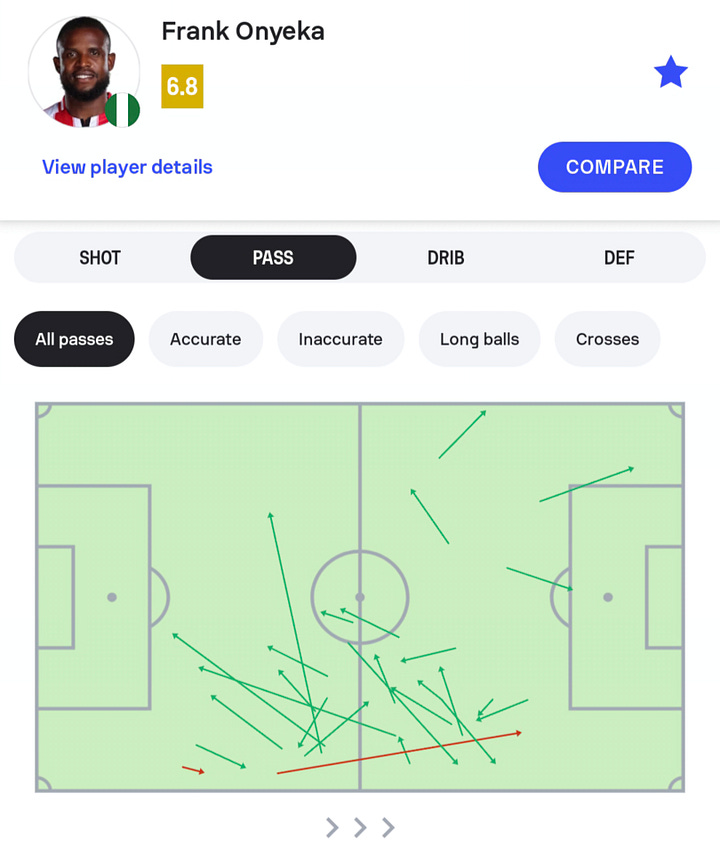

While there is no lack of enthusiasm to the team’s efforts against the ball, there is more to pressing than simply swarming the ball. There are technical details – distance, triggers, timing – that remain incomplete, and this leads to a lot of wasted energy. There are also rest defence concerns: whereas the current football meta is dominated by a defensive ‘net’ of five players (four, at the absolute worst), Chelle often has just three, comprising the centre-backs and Wilfred Ndidi. The captain is the lone Nigerian constant in the more eye-catching defensive metrics (tackling, interceptions), and actually leads the tournament for fouls despite sitting out the game against Uganda. Clever tactical fouling is, of course, a widely used tactic, but the frequency of them is telling. These interventions are, often, a consequence of the knowledge that there is far too much ground to cover. It was telling that, following the inclusion of Frank Onyeka against Tunisia, Ndidi went from committing seven fouls against Tanzania to just four.

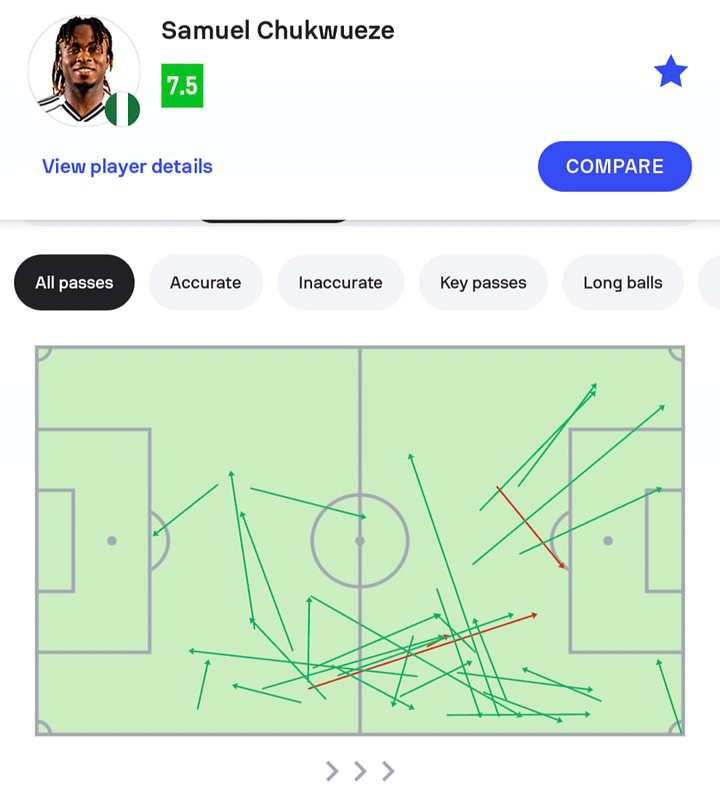

It now appears that the right centre-midfield spot holds the key to Nigeria’s flexibility. Samuel Chukwueze as the attacking option (albeit with an inverting brief for the right-back), Onyeka as the defensively responsible option, and Fisayo Dele-Bashiru as something in-between. As the tournament enters the crunch and the quality of opposition improves, it is likely the Brentford man will get the nod more often than not from here on out, and rightly so. That does not mean, however, that the desired alchemy has been found. The drawback, as touched upon earlier, is that, in picking Onyeka, Iwobi becomes a single point of failure for this side.

The Fulham midfielder has been without a doubt one of the leading players in the tournament, controlling and splitting lines in equal measure, and has formed a telepathic understanding with Ademola Lookman. Aside from him (and, to a lesser but welcome degree, Calvin Bassey), there are few reliable means for the Super Eagles to get the ball into the final third. It is equal parts intriguing and terrifying to think what might happen against an opponent that sics an attack dog on Iwobi; what would the effect of that be? Is this technical crew equipped to not just respond to that scenario, but also exploit the gaps that might open up?

They very well might be, but diagnosing the problem is one thing; recognising the fix is another; pulling the correct tool is yet another. As earlier stated, Chelle rightly realises the toll of his system, hence the switch to a flat midfield four later on in matches, ostensibly to facilitate a move to a deeper block. The thinking is sound, but the execution has left a lot to be desired in two distinct ways. First, a midfield pairing of Ndidi and Iwobi lacks some athleticism at the best of times, never mind when both have been running for 75 minutes. Second, as was evident against Tunisia, the choice of Chidera Ejuke to fulfil what was, essentially, a defensive brief, was puzzling in the utmost. (Interestingly, against Tanzania, it was Dele-Bashiru utilised in that role, a much better, more disciplined fit to aid ball retention.)

The Super Eagles held on by the skin of their teeth in both instances, but it is precisely that sort of decision-making that could prove the difference from this point on, with the margin for error drastically reduced. As far as appearances go, it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck all right. However, it is in the pressured, rarefied air of knockout football that the true measure of this side – elite or not? Contender or pretender? – will be properly determined.

Sound analysis as always.

Beautifully written.